Terrence Handscomb – 18 February, 2024

The politics of recognition provides critical protection to all art that bears the earnest marks of personal identity. Yet it is on the battle ground of perfidy, where symbolic battle regularly collapses into mockery, deprecation and retaliation, that the power of extrinsic narrative is born to rise up and dominate art; more so when fomented by the incendiary force of activism.

Kua ngā tohunga o neherā, he tapu, he wehi …

tēnā ko ō muri nei he hangarau ngā mahi! (1.)

There is alocal strain of decolonisation theory which reduces the entire corpus of European philosophical, religious, cultural and scientific thought to that of binary orthodoxy. The complete history of Pākehā theology, philosophy, art, politics, economics and science entails principles of binary separation, which continue to privilege sovereign discourse over mātauranga Māori and the cultural and spiritual efficacy of indigenous storytelling.

Eurocentric cultural biases are the remnants of a brutal colonisation which failed to see, let alone respond to, the exigency of indigenous storytelling in which the proximity of Gods, ancestors, people and land is not disjointed, it is immanent. There is no binary separation between peoples, gods, and their ancestors. In New Zealand art, a radicalised version of this argument calls to replace Eurocentric art-critical biases and privileged historiographies with targeted indigenous storytelling. Personal identity and group recognition narratives are the most important considerations in determining the meaning and value of art. This is because the principles of binary separation are so deeply embedded in Pākehā thinking that non-indigenous critics, curators and art administrators will never fully understand the intrinsic cohesiveness and communitarian principles that underlie contemporary indigenous art. Pākehā are therefore in no position to judge it.

To a certain extent this is true, because the assessment of art is fundamentally subjective and prone to the havoc stirred up by complex cognitive biases. But it is also true that in a world trammelled by global hegemony, under which “binary” thought - presumably this means the philosophically contested duality of ego and subject, of mind and body, of cogitatio and esse, of thought and being—continues to dominate art and politics, the unspoken heresies he iti te ao Māori, he iti te ao toi o Aotearoa are simple geopolitical truisms.

But from the depth of artistic cohesion where indigeneity remains uncolonised and words, gods, ancestors and peoples are inexorably conjoint, a cry rises up … he rawe te ao Māori, he rawe ngā Atua, he rawe ōku Tūpuna, he rawe Ahau! … and no one will say anything against it because in that moment of absolute profundity, words, art, things and gods are inseparable. Yet very little contemporary art—indigenous or otherwise—in this country has been truly decolonised to a point where it is immune from the perversion of sovereign power in its most pervasive form: the promise of capital prosperity and the seduction of artist recognition, otherwise known as success! If decolonised art is to differ from its colonising antecedents, then it must allay the propensity of all contemporary art to take root in the vast hollows of visual tropism that reiterate all that has gone before, albeit in novel ways.

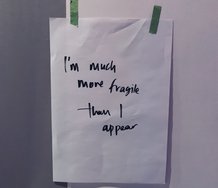

Few artists possess identity stories that are culturally immune to the various forms of what is becoming increasingly known as cognitive empathy deficit syndrome—the refusal to see where the other person is coming from—that force such stories to burgeon in semiotic battlefields where the signs of power infiltrate everything. As the power of art moves from things to words it enters a contested zone where advocacy, reprisal, and derision form an immense enterprise of deterrence. Making a stand on such a battleground requires no more ethical engagement than to either condemn or approve. (2.) To meet an adversary on neutral ground is tantamount to surrendering agency. On this battle field, reasoned critical debate is rendered dated, denunciatory and dangerous. Words need do little more than impose their own casuistry on all whom oppose them. When inflamed by the theatricality of outrage, the meaning and critical value of sovereign art is easily diminished. Under the threat of cancelation, there are few who dare stand up and object.

The politics of recognition provides critical protection to all art that bears the earnest marks of personal identity. Yet it is on the battle ground of perfidy, where symbolic battle regularly collapses into mockery, deprecation and retaliation, that the power of extrinsic narrative is born to rise up and dominate art; more so when fomented by the incendiary force of activism. Sovereign power will oppose any threat to its sovereignty, the privilege of its narratives, and the authority of its historicity. But when confronted by the thoroughly globalised progressive politics of recognition, and when backed up by the liberal ethics of semiotic compliance—language policing—such opposition is easily denounced, diminished, denuded and decolonised. A whole generation of artists and their advocates have discovered the power of cancellation and use it to quell any critical engagement with their work.

If critical art discourse fails to honour the politics of recognition and its attending principles of kindness, respect, inclusion and empathy, then ironically all hell will break loose. Cultural violence inevitably ensues at the slightest hint of sovereign pushback. For as long as the art of civil disagreement remains engulfed in the flames of tribalism, the plight of the pitiless art critic is one of incendiary doom. Because it has risen from the burnt ground of Eurocentric historiography, for New Zealand art history to be retold along the lines of indigenous storytelling requires little more intercession than to replace one set of narratological filters with another.

In Pacific rim countries where nineteenth-century European colonisation established large settler populations, the politics of recognition affords tremendous privilege and protection to all art that carries stories which oppose the critical mechanisms and structural biases of the coloniser. As the battle cry kei ngā kōrero te mana o te toi, kāore he mea kē atu! rings out with indubitable power and mana, it is nevertheless ironic that art which contests the sovereignty of the coloniser will routinely summon visual vocabularies that continue to speak with Eurocentric accents.

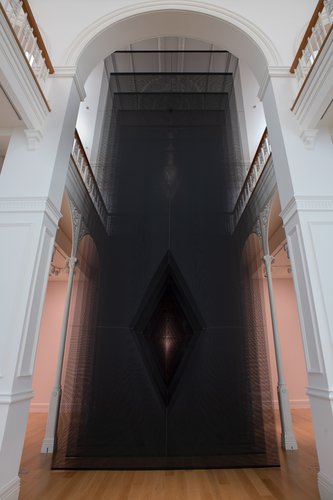

2021 Walters Prize winner Atapō (2020, installation) by Mata Aho Collective and Maureen Lander springs to mind. Despite its exquisitely chosen materials—insect mesh, wool, muka, cotton—the materiality of the entire work, its white-box installation and its institutional milieu quietly whisper in the voice of the coloniser: “high modernism!”

Engari! Ko te whitinga o te rā, ka whakangaro i te Atapō!

Materials and technologies that are yet to be fully decolonised—paint on canvas, metals, plastics, electricity, digital technology, institutional white-box display—when used without percipience, fail to allay the effects of two thousand years of Eurocentric art practice and its supporting historiography. Such materials and their histories come pre-packed in their own semiotic bubblewrap - otherwise known as the intrinsic bias of materials.

When contemporary indigenous art is dressed in the material garb of the coloniser, and no convincing Principle of Sufficient Translation—to paraphrase the renegade French “non philosopher” François Lauruelle—has been established, then the unilateral dislocation of indigeneity from the aesthetic biases of Eurocentric art can only be achieved when the forces of extrinsic story-telling rise up and smother everything. But simply overlaying the materials of the coloniser with extrinsic identity narratives does not decolonise the art … there will always be a semiotic remainder that will speak in unexpected ways.

Twenty-first century art has become so tightly integrated with the politics of recognition, diversity and inclusion, that large clusters of nominally decolonised art are rendered immune from the pointed barbs of art-critical discourses. This is partly because sovereign criticality is itself in the process of being decolonised and forced to readjust to supervening cultural imperatives. Moreover, incisive and unflattering art criticism has never sat comfortably with the bourgeois art market, which quietly conspires to silence any art criticism which does not serve the efficacy of capital exchange—otherwise known as the sale.

The close integration of art, cultural politics and capital furthermore explains why much nominally “decolonised” art is so successful in an art world that is both earnestly and superficially attempting to readdress the social and cultural mechanisms of its own privilege. Even when words and extrinsicality hold all the power, and the art that those words exalt looks just like everything else, no one bothers to ask why?

Terrence Handscomb, Āwhitu, Manukau Heads, December 2023

(1.)”The tohunga of contemporary times practice trickery, not like the tohunga of olden times who were tapu and frightening - those of today practise chicanery.”

This text translates and paraphrases an excerpt from the Maori language newspaper Te Pipiwharauroa (1 March 1900, p. 9). The issue discussed the annual hui of Te Kotahitanga o te Aute, at the Pāpāwai Whare, Hūpēnui/Greytown. Te Kotahitanga o te Aute was an autonomous Māori parliament which convened annually between 1892 and 1902.

The original excerpt reads:

Ko nga tohunga o muri nei he tinihanga noa iho a ratou mahi, kaore i rite ki nga tohunga o nehera, he tapu, he wehi, tena ko o muri nei he hangarau nga mabi, he whai mana, he whai ingoa.

(2.) Cf. Judith Butler, “The Compass of Mourning”, The London Review of Books. Vol. 45 No. 20 - 19 October 2023. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n20/judith-butler/the-compass-of-mourning

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Here is an informative article by Erin Johnson (in Stuff) on Mataaho and their intricate prize-winning work in Venice. https://www.stuff.co.nz/nz-news/350252377/mataaho-collective-win-top-award-venice-biennale

Ralph Paine

Regarding the technical plane: why is it that neither muskets nor smart phones, printing presses nor combustion engines, the alphabet ...

Ralph Paine

Second Variation of a Comment As Jorge Luis Borges puts it: “Every person is two persons, and the real one ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 3 comments.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 10:33 a.m. 25 February, 2024 #

Second Variation of a Comment

As Jorge Luis Borges puts it: “Every person is two persons, and the real one is the other.” So perhaps we’re all dual ethnographic participants now, at the same time both Observers and Informants, Natives and Strangers. All of us sitting on some glorious surf-fringed beach making field notes-to-self; gazing at the other while the other gazes back. Perhaps relations between the Māori world and the Pakeha world are themselves fluid, multiple, and non-binary. Why not? Given this scenario, the two worlds will co-condition each other, but only as Possible Worlds. Swiftly, it’s as if we’ve embarked on a mutually constitutive conceptual adventure together, an experiment in the decolonisation of thought: Multi-perspectival Moana.

And so along the way, beneath the sun, beneath the moon and the stars, beneath the filigreed canopy, each world will keep on keeping on as the other world’s other, that is to say, as its virtual transformative principle. By embarking, by entering into fluid, multiple, and non-binary relations—fractal between-twos, so to speak—the Māori world and the Pakeha world will sur-face together, cross over, entwine, interweave, but always via the equivocal possibility of a becoming-other, a process which always returns to us an image in which we are unrecognisable to ourselves.

Yet caution: NONE OF THIS HAS BEEN PLAYED OUT IN ADVANCE. The other world’s other is only a Possible World. That is to say, not a destiny nor an illusion nor a fantasy, but rather a virtuality. No world is capable of actualising its virtual other. No world is capable of expressing its other Possible World. The Māori world expresses the Māori world. The Pakeha world expresses the Pakeha world. Tautologies? Yes, but dynamic and very powerful ones. Meaning: each world remains coextensive with its own implicit and autopoietic values, languages, myths, genealogies, art, political formations, divisions of labour/models of work, cosmology, etc. and continues to express itself via these. Hence: a world is not actualised via some predetermined technical plane. A world is actualised via its expressions. Yet by also maintaining the implicit possibility of another world, each world can certainly think with or alongside this possibility and thus mutate and rearrange itself, if it so chooses.

Ralph Paine, 10:34 a.m. 25 February, 2024 #

Regarding the technical plane: why is it that neither muskets nor smart phones, printing presses nor combustion engines, the alphabet nor double entry bookkeeping, paint nor canvas, etc. have destroyed the Māori world? How is it that the Māori world and the Pakeha world can share a common technical plane and at the same time maintain their own implicit and autopoietic values, languages, etc.? In somewhat counter-intuitive manner, perhaps the answer lies in saying that the technical plane is also a virtuality; that is to say, not a virtual ‘world’ but rather a virtuality of technique, a generic plane of materiality and technical potential that both worlds can participate in helping to form, select from, and use in order to enhance the efficacy of their expressions.

Problem: how to guide this forming, choosing, and usage toward reciprocity/utu? And likewise, how to venture that the mutually constitutive conceptual adventure (as above) be conducted under the constellation of the gift/hau? In other words, how to always take so as to give, give so as to take—un-greedily? It is said that the Waitangi Process acts as the provider of such mutual guidance and generosity. Hence: under the auspices of said process, a co-governed art institution is conceived as entirely Māori and at the same time Pakeha, entirely Pakeha and at the same time Māori.

Mata Aho Collective and Maureen Lander’s Atapō is an expression of the Māori world. Already it can bind its virtual day to its virtual night in any Possible World whatever.

John Hurrell, 9:22 a.m. 23 April, 2024 #

Here is an informative article by Erin Johnson (in Stuff) on Mataaho and their intricate prize-winning work in Venice. https://www.stuff.co.nz/nz-news/350252377/mataaho-collective-win-top-award-venice-biennale

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.