Peter Ireland – 4 March, 2016

The historical artifact model of photographic shows, however worthily intentioned and no matter how well done, can so easily convey a fustiness off-putting to viewers. The genius of this multi-layered display is its thorough engagement with museum visitors. No one in the exhibition gallery for even a short time could fail to notice the effect of the images on viewers: there is close looking, animated discussion and attention paid to all aspects of this intriguing and comprehensive show.

Gisborne

Solo show

William F Crawford: photographic landscape artist

Curated by Dudley Meadows,

27 November 2015 - 3 April 2016

Photography’s a bit like notions of “bi-culturalism” - all right, but only up to a point. Acceptance of both - photography in the art world and bi-culturalism in the social/political sphere - has its limits. (Where the art world and the social/political sphere meet there’s lip-service paid to bi-culturalism - institutions now have added Maori names, but structurally and practically the art galleries and museums remain firmly in the hands of the majority culture.)

Even though, over the past three decades, the photographic medium has received admission to the art pantheon and collected widely by the art institutions, a self-serving selectiveness has limited access to a convenient creature called art photography. It’s mostly imagery from the 1970s on because that’s when contemporary photography took its own Great Leap Forward (1), but institutions with deeper collections include images from as far back as the later 19th century when the first self-consciously “art photography” began with an international movement called Pictorialism. But, the rest of photography is left out in the cold.

Of course, in the case of museums it’s been collected along with pots and pans, crinolines and the weirder instances of human social/cultural production to chart the passage of time and track the outer boundaries of human desires and imagination. The only time this huge archive can elbow its way into the exhibition programmes of galleries and museums is when certain photographers - such as the Burton Brothers - are seen to have been historically significant in some way, but even then appearances have been rare.

Frank Denton’s work was profiled at Whanganui’s Sarjeant in 2001, in 2004 the Auckland Art Gallery exhibited John Kinder’s work (his being helped by being a painter too - mostly from his photographs), and in the same year the Christchurch Art Gallery showed, and toured nationally, George Valentine’s work. During the years the National Library in Wellington had a gallery worthy of the name - 1987-2010 - historical photography from the Turnbull Library’s extensive collection was often seen there. But again, firmly locked into the context of historical artifact.

Increasingly, there are collectors here of contemporary ‘art photography’, but it’s still extremely rare to find collectors interested in historical photography. The lead given in the 1970s by the likes of Bill Main, Marshall Seifert and Peter McLeavey was almost never taken up. From the 1980s, John Gow at John Leech Gallery in Auckland was this country’s only major dealer interested in historical photography - more recently in collaboration with the indefatigable Michael Graham-Stewart - but since Leech’s closed in 2011 there has been no sign that Gow Langsford, as mother ship, might in any way pick up the slack. Indeed, given this dealer’s strongly contemporary international art brand, such an eventuality would seem highly unlikely.

So, the historical artifact model remains firmly in place, an airless room were possibility seems stifled by the lack of imaginative curatorial oxygen. It’s not as if there’s any lack of pictorial material though: this country’s archives are full to over-flowing with imagery not only vividly connected to our volatile history but capable of engaging with New Zealanders now. It’s all very well for the professionals to treat this great resource as merely a source of academic plunder - as if the imagery existed solely to grease their careers - but, their continuing to operate on such narrow assumptions is hardly testament to a scenario where imagination might outstrip ambition.

The Tairawhiti Museum is a small, rather meagrely-resourced institution perched at the north-eastern corner of New Zealand, but its small scale gives it flexibility and its committed staff can make things happen. The current exhibition of William Crawford’s work is testament to energy, flair and imagination. Their extensive Crawford archive itself has an interesting history. Then Gisborne resident, John Philip Crawford Gully, is Crawford’s great-grandson (and his great, great grandfather is the notable 19th century artist John Gully), and he and his wife Jen inherited thousands of Crawford’s negatives, which, after some sorting, they gifted to the then Gisborne Museum & Arts Centre in 1978. The museum’s resident historian, Shelia Robinson, did further work on the collection, and in 1990 published a book based on Crawford’s images called Gisborne Exposed (2). As the title indicates, it was more about Gisborne than about Crawford’s work, so the subject matter of his photographs was paramount and consequently the images were often cropped mercilessly, a process not at all improved by the quality of the printing. But it was a start.

Since then, the now Tairawhiti Museum’s resident photographer and curator of this show, Dudley Meadows, has not only further sorted the material and printed off many more images, but further additions to the collection have been made. This exhibition, partly, is to celebrate this achievement, and the focus now is working towards a publication that would extend the celebration and finally give William Crawford something of his due.

The historical artifact model of photographic shows, however worthily intentioned and no matter how well done, can so easily convey a fustiness off-putting to viewers. The genius of this multi-layered display is its thorough engagement with museum visitors. No one in the exhibition gallery for even a short time could fail to notice the effect of the images on viewers: there is close looking, animated discussion and attention paid to all aspects of this intriguing and comprehensive show.

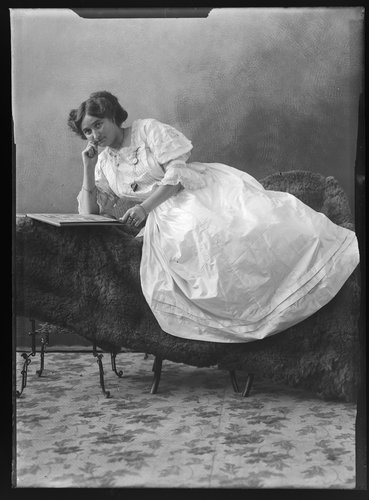

There are six distinct structural elements to William F Crawford. Firstly, spread thoughout the space are about 40 large reproductions illustrating the range of the photographer’s work - mostly his landscapes (both documentary and “artistic”) - complemented by a wall, hung salon-style, of 30 smaller images of his studio portraits, again illustrating the range of his practice.

Secondly, there’s a section of small groups of images - four to six - personally selected by various friends of the museum who have contributed their own labels. Galleries and museums can be fiercely protective about their labelling (usually under the guise of “professionalism”) and it’s very rare indeed they’re not “in-house”. Tairawhiti’s brave move is imaginative and refreshing, exchanging institutional anonymity for individual voices, undoubtedly an element in the exhibition’s engagement. A small, modestly-produced booklet containing the images with the selectors’ commentaries is available free for the show’s visitors.

Thirdly, the show’s curator has ‘stitched’ together - with the help of modern technology - several sequential Crawford landscape/birds-eye panoramas, realising what was surely the photographer’s intention, and has fixed the long prints to walls curved at just the right degree to replicate the experience of the eye’s natural scanning, “seeing” the view in the round, and not just flat.

Fourthly, the images are placed in the context of a range of historical material relating to Crawford’s family life and professional practice: family photographs, cameras, tripods, glass plates and the bags they were carried in, actual prints from his studio, albums of them, his card, newspaper advertisements, receipts and so on - an assemblage vividly conveying the life and times of a later 19th century photographer.

Fifthly, there’s a Magic Lantern Show, a series of slides covering Gisborne’s social life and its geographic hinterland as captured by Crawford’s seemingly insatiable eye.

Finally, and perhaps the most popular element of the show, there’s a backdrop (a very large reproduction of an image of the bush-lined “road” - just a track, really - to Wairoa), a large period carpet and period chair set in front of it, and a cane basket full of, let’s say, periodic clothing in which visitors may dress up and pose, entering into the spirit of standard studio practice in Crawford’s time. Museum purists may scoff at this element of the exhibition, but it sits comfortably within the whole and, indeed, within the contemporary phenomenon of the selfie. Crawford himself seems to have had a healthy sense of humour, and it’s easy to imagine him approving of this dressing up and having fun.

Hats off to the Tairawhiti Museum for generating this comprehensive, timely and ground-breaking exhibition, and to its curator Dudley Meadows for curating, on a probably tiny budget, a photographic show any serious institution could be proud of. It’s a model of its kind.

Peter Ireland

(1) See Nina Seja (and others) PhotoForum at 40, Rim Books, Auckland, 2014.

(2) Gisborne Exposed: the photographs of William Crawford, 1874-1913, compiled by Shelia Robinson, Te Rau Press, Gisborne (in association with the Gisborne Museum & Arts Centre), 1990.

Other Crawford-related material can be found in the New Zealand Journal of Photography no.52, Spring 2003, a portfolio of a dozen images entitled “Crawford’s Women”, and this writer’s piece “The Artifice of Realism: the studio portraits of William Crawford 1911-1913”, Art New Zealand 74, Autumn 1995, pp 87-89.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.