Peter Dornauf – 6 May, 2015

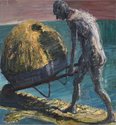

We are back with the neo-expressionists of the eighties. Such a glutinous, clotted yet adroit control provides a tense drama of scooping and gouging across the canvas - to match that of the taut, grim and obdurate narrative played out in each scene. The paintings become a theatre of excavation in order to describe an enactment of human endurance: life, pain, joy, debilitation and death.

Hamilton

Euan MacLeod

The Painter in the Painting

Curated by Gregory O’Brien

28 March - 5 July 2015

Art, like a lot else, is not above fashion. It is still a prisoner of trends where hot and not hot continue to prevail. This is not news, of course, but it’s a troubling conundrum. Post 1970, the “star system” was abolished, but even now, after the plural has been valorised and roundly applauded, there remains a persistent disavowal among the gate keepers and cognoscenti toward art styles that are deemed out of date.

The figure, for example, seems to have gone out of vogue in paint, treated more often these days in photography and collage. The expressionist brush-stoke is also a thing of the past, relegated to the era of the 1980’s where it had a brief resurgence through the work of the neo-expressionists.

Both these demoted practices are found in the work of expat New Zealander, Euan MacLeod, unconcerned that the tide has gone out on this stuff, despite all the endless talk of the end of hierarchies. Such contradiction pertains in a world forever in search of fresh meat.

What has also become unfashionable is a kind of thinking that ran parallel with the expressionist trope in the 1940’s and 50’s, namely the philosophy of existentialism, made popular by Jean Paul Sartre in the post war period. However that has not deterred MacLeod from continuing his practice, begun in the 1980’s, that both in style and perhaps philosophical substance employ and reflect on stuff that is no longer the rage. Nor should it.

Born in Christchurch in 1956, he moved to Sydney in 1981, where he continues to live and paint. However his links with New Zealand still run deep and the current exhibition at the Waikato Museum of 50 large and smaller paintings, the first major survey of his work in New Zealand, covering material from 1984 to 2013, reveals a consistency of style and content quintessentially MacLeod.

Curated by Gregory O’Brien, the “Man Alone” Mulgan reference is made early in the blurb and the paintings certainly reflect such a reading. Single and solitary figures dominate rugged landscapes, often coastlines or mountainous regions. The latter seems to be a new departure for the artist, choosing the Alps as location, something rarely selected as a subject by artists today.

MacLeod’s treatment is in the tough somewhat romantic mode both in style and compositional treatment. His lone figure in, Above the Clouds, 2010, for instance, recalls Capsar David Friedrich’s, Lone Wandering above a Sea of Fog, 1818, minus, however, the mystic overtones of the German. His mountain top figure surveys a vista of clouds and mountain ranges drifting off into the distance, feet planted solid in the snow like some swarthy Ed Hillary type swearing under his breath about knocking the bastard off.

There’s no examination of the sublime or connection with spiritual forces here. What we are presented with encompasses the stark and brutal matter-of-factness of it all. Similarly does an equally large work, Rocks and Snow, 2012, that pictures a single mountaineer making his way up the snowline, past monumental boulders, dwarfed by the magnitude of things but doggedly and stoically continuing on.

MacLeod’s treatment is one seldom employed today. It involves a heavy impasto handling of paint trowelled on to create a thick layering of pigment that runs and congeals in a dense textural conglomeration of scored, slashed, carved and smeared viscous surfaces.

We are back with the neo-expressionists of the eighties. Such a glutinous, clotted yet adroit control provides a tense drama of scooping and gouging across the canvas - to match that of the taut, grim and obdurate narrative played out in each scene. The paintings become a theatre of excavation in order to describe an enactment of human endurance: life, pain, joy, debilitation and death.

In fact the artist’s particular delineation of man alone in a forbidding landscape has something of the flavour found in Denis Glover’s poem, To the Coast.

When God made this place

He made mountains and fissures

Hostile, vicious, and turned

Away His face.

MacLeod’s figures are somewhat Giacometti-like, often naked, stripped back to the bone, bare-forked creatures, a little like King Lear howling in the wilderness, or if not quite howling, then mute with stoic fortitude and completely without redemption; because God is dead.

The latest piece in the exhibition, Hearsay (2013), underlines such a predicament. Displayed in the middle of the gallery, in concertina book format, large black and white etchings are propped up that repeat the figurative imagery of the paintings as well as being accompanied by tortured texts. The texts take the form of a litany, statement and response mimicking a kind of forbidding catechism:

I don’t want to die.

Will die.

I don’t want to lose you.

I will lose you.

I remember there was once a God.

I remember fragrant rice.

I will grow wild.

I remember the dawn.

There will be no more.

This grim existential script complements images of death complete with falling bodies and eroded figures sprawled across planks that recall the desperate forms that inhabit the rear end of The Raft of Medusa.

The boat motif is pervasive throughout the exhibition. The symbolism of life journey is evoked in many of the works - Boatman 2 (2005), Two in a Boat (2007), Boat Above Submerged Figure (2012) where naked figures become emblematic of universal refrains. It’s a motif the artist returns to many times, loaded with portent, sometimes conjuring Bocklin or Dante, but with a twentieth century take: bodies in a reductive state, scratched and serrated, paint dribbled like rain. And the landscapes are treated like primordial presences, elemental and rudimentary like the figures that inhabit them. The boat as coffin becomes pronounced in the work depicting his dead father lying naked in one, propped up on a platform inside the family lounge.

This is one of the few paintings in the show that deal with things on a more domestic level. The other, Dinner Study (2006) is more prosaic; a family at mealtime, sitting round the table. But MacLeod invests the scene with a power equal to that of van Gogh’s Potato Eaters.

There is much in MacLeod that confronts the drama of human life in the age of unbelief while attempting to stare it down via an unflinching acceptance of its sheer brutal isness. One could say perhaps, “Child Rowland to the dark tower came”, and with his minimalist palette of moody, muddy browns, blues, yellows, blacks and greys, the artist looked at it and did not look away.

Peter Dornauf

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.