Peter Ireland – 21 January, 2013

Were the “Painting” of Two Hundred Years of New Zealand Painting to be replaced by “Painters”, the book might have made more sense philosophically because, essentially it was, and remains, more about painters than painting. Its first edition was reprinted eleven years later in 1982, without any alteration to the text or reproductions.

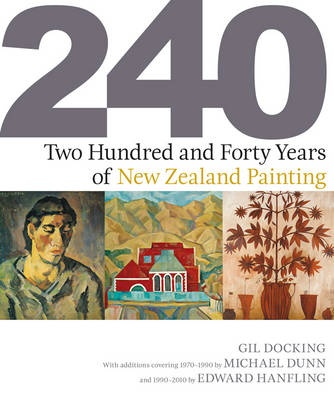

Two Hundred and Forty Years of New Zealand Painting

Gil Docking, Michael Dunn and Edward Hanfling

280pp, 170 illustrations

David Bateman, 2012

RRP $99.99

1 ANTECEDENTS: 1940-1969

The historian Keith Sinclair was fond of telling the story of his interview in 1939 with the Auckland Teachers’ College application committee when they asked him if he had any special interests. He replied “Yes, reading New Zealand literature” and they all burst out laughing. He might just as well have admitted an interest in centaurs or the Loch Ness Monster. Could such a thing exist? E H McCormick probably had a similar audience in mind when, around the same time, he set out on his Letters and Art in New Zealand for the Centennial Surveys series in 1940. The prevailing educated, widespread opinion was that real art happened somewhere else, and whatever humble productions might result here could only be pale imitations of painting abroad. Which happened to be largely true.

Nationalism’s had a hard time in the subsequent story more recently, but had it not been for committed public servants such as Joe Heenan at Internal Affairs envisioning the Centennial Surveys, believing it was time to begin charting our own historical experience, what published art history we have might’ve begun still later, and possibly in less able hands than Eric McCormick’s.

Lacking any local models McCormick had to find his own way. There was not much to go by, even in Australia either. The notion of history is predicated on constructing a narrative that, however crudely or even misleadingly, tries to make sense of a mass of seemingly unrelated data. And, no matter how stringent the discipline or how rigorous the writer may be, histories always bear the stamp of their time, embedding all the assumptions, prejudices and aspirations implicit in being alive. As with many intellectuals formed in the 1920s and ‘30s, McCormick’s outlook was basically socialist, and this was reflected in the framework around which he chose to tell his story. This is the first sentence of the Preface: “While I have attempted some evaluation of New Zealand letters and art in the following essay, my chief aim has been to bring out their relation to social changes in the years since European discovery”.

In later years McCormick’s focus may have shifted towards the art end of the spectrum - his enduring work on Frances Hodgkins, for instance - but in 1940 his interests were primarily literary, and this was reflected in his Centennial Survey: at least two-thirds of the narrative centred on the letters, and the literary emphasis spilled over into his interpretations and assessments of the art content. He admitted as much in his Preface: “… the sections on art may best be regarded as pendants to the larger literary undertaking”. The Preface also stated: “The terms used in the discussion of graphic art (for other branches have had to be ignored) are a ‘literary’ observer’s, not those of an artist or critic of art …”. This has been an ongoing feature of New Zealand art writing, from C N Baeyertz through A R D Fairburn and Charles Brasch, to Ian Wedde, Gregory O’Brien and David Eggleton, as has the foundational approach of “the years since European discovery”, as well as the corralling of painting into a history unconnected with those “other branches” of art.

Another official Centennial project was an ambitious survey of New Zealand art, 355 works by 222 artists curated by A H McLintock and toured nationally over 1939 and 1940. McLintock’s essay was, however, more descriptive than McCormick’s attempt at a broader view analysis, the catalogue largely a series of individual artist biographies held together by a story of some conservatism, including the following observation: “Fortunately, perhaps, there was little experimenting with the fantasies of the more extreme schools of painting”. Take that, Modernism! He continues in a similar vein with a comment that, at the end, nonetheless connected with McCormick’s approach: “The experiments somewhat defiantly conducted were in the main merely imitative and rested on no deep social basis”.

McCormick’s pioneering effort was built on in a typically kiwi DIY fashion for another two decades, an ad hoc accumulation of information ranging from articles in Art in New Zealand - some of which remain enduring - to the odd public gallery publication, a process which began to resemble something of a focused and professional effort in the 1950s at the Auckland Art Gallery when director Peter Tomory, an Englishman, encouraged staff such as Hamish Keith and Colin McCahon to mount small shows about earlier artists working in New Zealand. The modest publications accompanying these were the bricks forming the foundation of a New Zealand art history. There were probably committees around then who laughed at the idea of that too.

In the 1960s the Gallery developed a Modernist focus and attention was given to more contemporary artists. For instance, McCahon and Woollaston were given their first joint survey in 1963. In the meantime, though, the Gallery’s estimable Quarterly was quietly adding to the sum total of knowledge, its regular production of news and opinion adding materially to the critical mass, the one institution in the country taking this construction seriously.

In 1968 there appeared a modest volume published by Reeds (also available in three separate parts) New Zealand Art: Painting 1827-1967 by three Auckland Art Gallery staff: Keith, Tomory and Mark Young, consisting of 99 pages with 24 reproductions in colour and 53 in black and white. Each writer took a period of decades, wrote an introductory essay followed by a one-per-page reproduction accompanied by biographical notes relating to the respective artist. This small but significant book is perhaps best remembered by a resulting spat in the pages of Ascent between Charles Brasch and Tomory. But that’s another story….

2 BROWN & KEITH: 1969

Hamish Keith had also teamed up with another Gallery employee, librarian Gordon H Brown, and they produced the more ambitious An Introduction to New Zealand Painting1839-1967 published in 1969, the first serious attempt between hard covers of a comprehensive account of painting in this country. (Not to be left out, McCahon provided the jacket design.) Brown and Keith were aware of the pioneering nature of their venture, hence the tentative Introduction of the title. It had been thirty years since McCormick’s book, a generation had passed and the whole intellectual basis for such an undertaking had changed: McCormick’s social framework was replaced by an art historical one. This was both an advantage, for obvious reasons, and a disadvantage, given the perils of such a self-referencing structure where art ends up talking about art. Yet, within that structure Brown and Keith attempted to set the achievements of the featured artists inside a bigger historical picture, a context, an analytical approach important to keep in mind in view of what has been published subsequently.

In the 1980s the book became mired in a controversy about an alleged “hard light” theory, but even the protagonist, Francis Pound, conceded - against his severe reservations - that “The material brought together in [this book] is … both ample and well organised. Of a chaos of fact, a clear picture has been made. Its importance in forming a picture of New Zealand painting … can hardly be over-estimated”. Despite all later critical assessment, Brown & Keith’s Introduction remains a cornerstone of our developing culture and a still-credible foundation for the house of New Zealand painting’s history.

3 DOCKING: 1971

At the time of the Introduction’s publication Tomory’s successor at the Gallery, Australian Gil Docking, was working away at another book which added a first floor to Brown and Keith’s foundations. But his confidently-titled Two Hundred Years of New Zealand Painting differed radically from the earlier book. Whereas Brown and Keith offered an analysis of the historical information, Docking’s was merely a synthesis of it. The earlier analytical approach placed individual artists within a framework of periods and movements whereas for Docking the individual artists largely provided the framework, probably making it seem more accessible as a reference tool. Probably too, its greater popularity was due to the more lavish reproductions and the impression of greater size. It’s only an impression; although Two Hundred Years is thicker and weightier, it’s because of heavier paper stock and tipped-in plates. It has 212 pages to the Introduction’s 222.

At this point it’s necessary to consider what such a history consists of and what it’s doing. There is such a pattern now of chapters starting with introductory paragraphs followed by consideration of individual artists one after the other that it’s become an automatically accepted way of outlining an art history. An imagined parallel example might throw some light on this pattern’s structural shortcomings. Take a more conventional historian such as James Belich and his account of the nineteenth-century land wars. What if such an account had chapters beginning with half a dozen paragraphs of general observations then followed by potted biographies of participants such as Rewi Maniapoto and Wiremu Kingi, George Grey, Generals Cameron, Chute and McDonnell, Te Kooti and Titokowaru et al, would such a clunky compilation have much credibility as history?

Of course, the staffage of the land wars’ stories never had to shoulder the burden of the Romantic artist myth (except, perhaps, when the likes of Te Kooti were written up as rebels) and so the narrative took easy precedence over the characters. Were the “Painting” of Two Hundred Years of New Zealand Painting to be replaced by “Painters”, the book might have made more sense philosophically because, essentially it was, and remains, more about painters than painting. This first edition was reprinted eleven years later in 1982, without any alteration to the text or reproductions.

There’s a curious aspect to this first edition always talked of and never written about, and one that must surely impact on any assessment of the writer’s critical judgement. One of the longest entries in the book - longer than that devoted to McCahon, for instance - was given over to an Australian-born painter Shay Docking who was domiciled temporarily in this country as the wife of the author. Her work had made no mark on this country’s art before her arrival, and bequeathed nothing to it after she left. The entry remains intact in all editions of the book to this day.

1982 also saw the publication of a revised and updated version of Brown & Keith’s Introduction to New Zealand Painting (there has been a reprint of the original 1969 version in 1975). This is thirty years ago, remember. The authors added a crucial and illuminating note: “To do justice to the varied and major developments in New Zealand painting since this book was first published in 1969 would require an entirely new work” (Italics added). This modest statement resembles the first report of icebergs in the North Atlantic and the ongoing publication of the Docking book the continuing passage of the Titanic across it.

4 DOCKING/DUNN: 1990

Another eight years on, in 1990, an enlarged edition appeared. The 1971 content remained unaltered and a new section covering the two decades between 1970 and 1990 was contributed by art historian Michael Dunn, adding to Docking’s bungalow an upper story consisting of 36 pages and introducing 23 new artists. A year later Dunn published his own Concise History of New Zealand Painting under an Australian imprint. This, crucially, followed the Brown & Keith model more than the Docking model in two respects: it was more analysis than synthesis, and it avoided the more chronological approach followed by Docking. Dunn stated in the Introduction: “Rather than follow a strictly chronological sequence I have looked at categories of painting such as landscape, paintings of the Maori or abstraction. This approach has been adopted with some attention to the matter of coherence and period”.

It’s instructive to compare parallel treatments of individual painters by Dunn in his 1990 contribution to Docking and in his own 1991 book. Even allowing for apparently more room in the latter (it’s hard to quantify exactly, given the different structures) there is indeed “attention to the matter of coherence and period” lacking in his Docking additions. The somewhat show-and-tell quality of the Docking approach had clearly cramped Dunn’s style. By 1990, as a history of art, Two Hundred Years of New Zealand Painting had become increasingly redundant, for two principal reasons.

Firstly, in 1971, practically all the major artists were painters, so that an account of their production gave a reasonably legitimate historical perspective to art activity generally. That was no longer the case, and increasingly so, from the mid-1980s, even before Dunn’s first floor got added to the Docking bungalow.

Secondly, the fact that the 1971 text - covering two centuries of endeavour - had not been updated at all (except in very, very minor instances) renders it, increasingly, of dubious historical use on two counts: in the past forty years the discipline of art history has evolved significantly - if not radically - on many fronts, not just in the way the past is (re)assessed but how the present is evaluated. The various publishers of the Docking series appear to be intent on ignoring this, with their writers necessarily complicit in the evasion too. The other count is simply that some artists, those still working around 1971, have been so poorly served by this failure to update their entries as to make the continued association of the word history to this enterprise absolutely risible.

Take the case of Pat Hanly. In 1971 he was, roughly, halfway through his career, and yet in 240 Years of New Zealand Painting the only alteration to the 1971 text regarding him is the addition of his 2004 death date. No mention of anything after his Piccasoesque Girl Asleep series: nothing about his murals, nothing about the Torsos series, nothing about the Molecular series, the Energy series, the Pacific Condition or Golden Age series. This may be a coincidence, but on the Arts Foundation’s website there’s a gap between 1971 and 2004 in Hanly’s biography too. But at least he did get a death date in the Hanfling update; it’s more than the late Ted Bracey gets.

Even more bizarre is the case of Gordon Walters. Not only does he suffer the same fate as Hanly, but he suffers it at the hands of a writer who curated both major Walters’ retrospectives. Unaccountably, Dunn’s 1990 update of Docking fails to mention Walters at all, but his own 2003 revised history of New Zealand painting devotes four pages to the artist with three reproductions. Go figure. These instances may be amongst the most glaring shortcomings, but they’re far from being unusual. The new edition, for instance, continues to assure us that Jeffrey Harris has lived in Melbourne since “the late 1980s”, when he returned to Dunedin in 2000. It’s not just a biographical detail either; his return a dozen years ago has had a significant impact on his work - a fact you’d be forgiven for thinking might have some vague interest for a history of painting.

Strangely for an artist not only widely considered to be, perhaps, this country’s a most significant artist, but one who produced his most magisterial work in his final decade, McCahon is allowed just one illustration after 1971, a 1985 work in the 1990 Dunn update. No mention of Woollaston after 1971 either - another late-career bloomer whose large works Above Wellington of 1985 and Tasman Bay 1928 (1974-5) are amongst the peaks of his achievement. Is this a history of painting or is it a history of omission?

5 DOCKING/DUNN/HANFLING: 2012

Another twenty-two years has gone by since the 1990 revision, but the original 1971 Docking text remains almost completely intact. The new writer, art historian Edward Hanfling, adds an attic to Docking and Dunn’s now two-storied bungalow, consisting of 28 pages and introducing 22 contemporary artists, but by this time the house historically has become uncertifiable as a dwelling.

But first, the good news. In the original and subsequent editions there were 80 reproductions in colour and 68 in black and white. In this latest edition all but six are in colour, and all the colour reproductions are now of much superior quality; the uniformly yellow cast which misrepresented so many of the works in earlier editions has finally been eliminated. The six reproductions still in black and white for various reasons are now of inferior quality - a clear case of horses for courses. This general advance is all very well, as long as you accept that the choice of reproductions and the values represented by those choices relate to four decades ago, within a bull’s roar of half a century. The same amount of time, incidentally, between James Nairn’s arrival in Dunedin in 1890 and Eric McCormick’s Centennial Survey in 1940. Once upon a time - when Victoria was on the throne and all was well with the Empire - such a static view of history was possible. Of course, then such a position had clear political advantage. But now, such a static view is not only unsustainable, it’s ridiculous, and any further imposition of it warps the narrative so wildly that it honours art less even more than it dishonours the publishing industry.

Publishing is fundamentally a commercial enterprise - unless you’re a Taschen or Alan Gibbs - and so the question of a market is central to the whole business. In the first chapter of the latest update - chapter six of the book - Hanfling writes: “The status of painting as the pre-eminent artistic medium has been challenged during the period from 1990 to 2010. Certainly the art market is awash with paintings, and many, probably most, dealer galleries find it easier to sell paintings than any other kind of art: they fit easily into domestic interiors; they are readily accepted as ‘art’; not likely to be confused with everyday items as some sculptures are; they carry associations of beauty, status and uniqueness”. Is this art history or a sales pitch? Material such as this could just as well have been written by an art dealer.

The writer contrasts this private commercial gallery situation with the public galleries and “alternative” spaces which, for the purposes of his argument, devote more support to what appears to be less accessible and more saleable contemporary art. Somehow this slightly artificial contrast - and the popular alienation it implies - is meant to justify the continuing publication of a book resembling a history of painting. At the beginning of the twenty-first century any such history involving contemporary art can only make sense if it’s in relation to those “other branches” of art McCormick referred to in his 1940 essay. That this, of course, may not be “practical” is perhaps telling us something, not so much about commercial risk as the conceptual viability and credibility of such grand projects as 240 Years of New Zealand Painting.

Moreover, this decade is witnessing a widespread disenchantment with the notion of national histories generally. It’s not just the ripple effect of globalization, but a greater realizing of the illumination implicit in the interconnectedness of aspects such as origins and developments inter-nationally. James Belich’s 2009 Replenishing the Earth is a fine example, the subtitle indicating the direction really innovative research is taking: the settler revolution and the rise of the anglo-world. Similarly, but with a more art-focused approach, Damian Skinner is studying the intersections of European visual high culture and first people’s customary practice throughout colonial situations in places such as Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

In his Introduction covering this whole new edition, Hanfling observes “At the forefront of my thinking was the problem of ‘audience’. … this book has been an entry point to New Zealand art for those who do not consider themselves as art aficionados, as well as being a reference book for those who do”. Overlooking why an audience might be considered a “problem”, it’s clear that the book fails as a useful and even credible reference work. Its latest author even hints at this further on in his Introduction, breezily suggesting that “Docking’s history is of interest now as a historical document” as if that had no bearing on the relevance of the “new” book. While there tends to be a perceptible shudder in the art world at mere mention of anything “popular”, it’s interesting to note that perhaps this country’s most popular contemporary artist, Dick Frizzell, is also not well-served here. Hanfling doesn’t mention him at all, but probably because he was covered by Dunn in the 1990 update, where he merits a mere 137 words and a small illustration of a landscape that’s less Frizzellian than Weeksian. Besides, by now, isn’t it a little cynical and somewhat patronising to assume that having a market means targeting schoolkids doing projects and punters combing dealer galleries for likely investment art?

Throughout the latest update of this book there’s not much contextual analysis beyond some journalistic generalities, and if there’s any synthesis involved it’s not easy to make out what it’s a synthesis of. Synthesis at least implies some sort of focus, a target, but with much of the information in the 2012 update there’s often a sense of blanks being fired into the air. If there’s any wider context, it’s the context of the Docking book itself. As unfashionable as such a wish might be, this lack of a wider context makes you yearn for the sort of social framework attempted by McCormick and McLintock back in the bad old days of 1940.

Hanfling clearly enjoys a degree of satisfaction from being perceived as maverick - his regular exhibition round-up column in Art New Zealand tends to suggest that - but quarterly comment in a magazine is not the same as compiling something with pretentions to history, and while maverickism may have its irresistible attractions, even Butch Cassidy knew it had to have a point. Take the following entry about Saskia Leek’s work: “[she] paints twee and kitsch pictures, but they have a particular edge to them because she paints this way deliberately and knowingly”. A writer such as Robert Leonard can make a point by applying seemingly pejorative descriptions, but it requires an intelligence such as his to make an illuminating point of it, not leaving the remark dangling lamely, pointlessly striking a pose. Writers in this field need to be historians of words as much as they’re historians of art, and the word kitsch is a Modernist term of derision having no credible application to Leek’s contemporary project, even ironically. Further, the whole issue of artist intention is a minefield, and the writer assuming that because the artist “paints this way deliberately and knowingly” it’s the end of the matter is staggeringly simplistic. The author’s oracular style suggests certainties when there is only speculation. Verisimilitude subsisting in the mere act of stating is usually reserved to the Almighty; the rest of us are obliged to provide evidence.

As with the recently-published Anthology of New Zealand Literature edited by Jane Stafford and Mark Williams, the temptation’s to focus any discussion on who’s in and who’s out. Ultimately it’s about arguing the relative merits of, say, the latest BMW or a reproduction Mini Cooper. But in the case of 240 Years of New Zealand Painting it doesn’t even matter now. To raise the Titanic analogy once more; wouldn’t it be better to be on almost any other ship?

6 NON-EUROPEAN PAINTING: 1769 -

One of the biggest social changes to occur in this country during the publishing history of the Docking book (and still being resisted in some quarters - Ian Wishart’s recent book The Great Divide being a pertinent example) has been the progress of what might be termed Maori self-determination. (It’s an interesting coincidence that the first major protest of modern times at Waitangi on the 6th February happened in the same year the Docking book was first published.) The focus is mostly on what this process means for Maori, but conversely, there is a lot meaning for Pakeha too - such as a quiet revisioning of concepts such as “European civilization” and what they might mean for us here and now.

The second paragraph of McLintock’s 1940 essay began with this: “It must not be forgotten that when the first Europeans arrived in New Zealand the country possessed in its Maori art a unique native culture …” and McCormick’s essay of the same year had this as its penultimate observation: “Whether in the next 100 years New Zealand will add anything great and distinctive to the tradition of European civilization will not be decided wholly in New Zealand nor wholly by New Zealanders”. The first constitutes an acknowledgement of the past that the second denies as having any relevance in the future. Well, history is full of surprises.

The Introduction to the first edition of Two Hundred Years of New Zealand Painting referred to Maori traditions of using “paint for staining their bodies, for painting designs on rafters, for colouring carvings and making images on the walls of rock shelters”. Docking concludes: “Although the Maori rock paintings are highly interesting, they are outside the scope of this study”. Considering what else he judged to be more interesting and within the scope of his book, the statement itself is more than “highly interesting”.

It’s indeed highly interesting that the Introduction to Brown and Keith’s 1969 book, uniquely for all these publications under discussion, makes no reference whatever to Maori art practice. Especially in view of one of its authors later making great claims as to his generating participation in the Te Maori project. After all, one supposes, there’s no reason that even the road to Damascus should not have a few twists and turns.

A year after New Zealand’s sesquicentennial in 1990, Michael Dunn’s Introduction to his Concise History of New Zealand Painting ends crisply with: “Traditional Maori art is not within the scope of this work”. Yet just thirteen years later in 2003 in the revised and enlarged edition the new Introduction begins with over a page devoted to Maori art practice plus an illustration of rock drawings. There’s a brief, broad outline paralleling Docking’s 1971 list, but it makes a connection with mid-twentieth century Modernist interest in the “primitive” - Theo Schoon’s part in this is not actually mentioned, perhaps to avoid the controversy of his well-intentioned vandalising of many ancient rock drawings. Dunn then links the later nineteenth century figurative innovation of painted wharenui with McCahon and Robyn Kahukiwa, and ends by observing: “By the 1960s the fertile interaction between traditional Maori art and contemporary European painting had evolved enormously”.

There’s an additional observation relating to the scope of the book that reveals just how circumstances can change in even just a few years. In explaining his decision to begin his history in 1840, Dunn stated: “But the works of artists like [Hodges and Earle] have only a tenuous link with the history of painting in New Zealand. Their works belong to the history of British art and it is only the subjects that are relevant here”. Overlooking the problematic distinction between the art and its subjects, the statement now has a rather curiously antique ring to it, demonstrating that it’s not art historians who make art history but the artists. In the two decades since Dunn wrote, many contemporary artists here from Tony de Lautour to Marian Maguire have, in fine Postmodernistic spirit, rifled through history’s box-room, re-appropriating imagery and styles from Tasman’s artists on, making the formerly irrelevant very relevant indeed. It’s a lovely case of the colonies cheekily doing a bit of unlicensed re-exporting. In 240 Years of New Zealand Painting none of this gets a mention, but Shay Docking still has her two-and-a half pages. Hello?

So, the Eurocentric focus of McCormick’s 1940 pioneering study lives on in the house of local art history. The list of activities in customary Maori art in Docking’s first Introduction all involved the application of paint - like, as in painting - but the sticking point seemed to be it wasn’t framed and on the wall. This requirement looks pretty quaint now when so much art production is framed only by context and ambition and is often located anywhere else but a wall. Yet the stricture on customary Maori art remains. Is this 2013 or what? How longer must Clio be left weeping in her dimly-lit corner?

Despite polite and sometimes desperately inclusive references to developments after Modernism by art historians, the framing of the house of art history is still very much Modernist radiata. For instance, any art with a political agenda - offending the movement’s purist ideology - accrued the Modernist sobriquet of “propaganda”, unless it was something like Guernica or John Heartfield montages (it’s all right dear, Mr Churchill won the war). One of the strongest pistons driving contemporary Maori art is a shamelessly focused political agenda, and again, while Hanfling notes this in passing, there is not the slightest inkling in the new edition of, firstly, what sort of change this might indicate and, secondly, what its implications might be. Bugger the Queen, it’s Long Live 1971.

The attic’s flooring of 240 Years of New Zealand Painting could’ve been matai, but it turns out to be only particle-board. In a section introducing the four Maori artists whose work he covers - Robyn Kahukiwa, Saffronn Te Ratana, Shane Cotton and Peter Robinson - Hanfling writes: “During the 1990s, with the growing awareness both of New Zealand’s bicultural history and increasing multicultural society, many artists sought to address issues of cultural identity, and to represent cross-cultural exchanges and encounters. Sometimes the intention was simply to assert the presence of a specific culture via symbols of references to beliefs or traditions. Some Maori artists took on a radical or activist political stance as part of their art. In other cases there was an attempt to highlight the complexity and instability of identity”. Even allowing for the necessity for generalisation, as information this conveys little more than might be expected from a competent feature article in, say the Sunday Star Times. Admittedly, there is more detail in each of the four entries for the specific artists, but it offers no penetrating insights as to the nature of their collective endeavour. Their being covered together implies there might be one.

The only artist identifying as Pacific that Hanfling includes is John Pule. Interestingly, in his 2003 history, Dunn includes 14 Maori and Pacific artists, as against Hanfling’s five in 2012. Moreover, the latter’s analysis of individual works, such as Te Ratana’s, tends to a formalist interpretation that risks missing the entire point of the artists’ raison d’etre.

Will there be a further updated 250 Years edition in another decade? Perhaps some newly-minted art historian is already making notes towards the 2040 bi-centennial Docking, attic dormers fit for a third century of European civilization? Nah, the thing’s had it. It’s a job for Gerry Brownlee.

Peter Ireland

Recent Comments

Andrew Paul Wood

I must admit to being most dissatisfied with Ed's lean-to. It was so chronologically and contextually at odds with the ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

Andrew Paul Wood, 2:42 p.m. 21 January, 2013 #

I must admit to being most dissatisfied with Ed's lean-to. It was so chronologically and contextually at odds with the previous sections in terms of who of the present was anointed (or ignored)and who of the past ended up being shoehorned into the present. If I may be permitted a brief act of linkwhority:

http://www.newzealandpainting.co.nz/2012/11/240-years-of-new-zealand-painting-review/

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.